- A total of 27 European countries went to the polls in early June to elect the 10th European Parliament (EP).

- Forecasts had suggested a distinct shift to the right, but overall, the centrist parties largely held their ground.

- On the basis of the election results, crypto policy can be expected to be challenging in the more fragmented EP, even if several MEPs active on digital assets issues were re-elected.

- Read more about the European elections and crypto policy.

The topline – what’s the outlook for crypto following the elections?

The European election results means there may be less focus on crypto. Should President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, secure a second term, then her focus on the ‘twin transformations’ (green and digital) would be enhanced and positive for crypto. Overall though, digitalization risks being a relatively less important topic for this new cycle compared to the last.

Also, there may be less financial services-focussed digital asset legislation, but the industry can link up with the competitiveness agenda, to promote the innovation and efficiency that technology can bring.

In terms of specific agenda items, officials are considering the following three issues: AI in FS, where there is an open consultation under way; tokenization; and a review of MiCA, which could include provisions on DeFI, NFTs and EU level supervision for CASPs.

Finally, a focus on implementation rather than more legislation is something the industry has been advocating for and seems to be gaining political traction. So a ‘less is more’ approach could well prevail.

Why were these elections important?

These elections were important because the EP effectively offers a direct link between Europe’s population and its institutions. Each country in the European Union is proportionally represented in the EP, ensuring the outcome of the EP elections reflects the will of the people.

On another level, EP elections offer the electorate a chance to send a message to their governments. Given broad dissatisfaction with politics throughout the union, particularly over divisive issues like immigration, just how much financial and military support Europe should give Ukraine, and the EU’s future, pundits were watching the results closely to get a sense of the direction of national politics as well as wider shifts in the bloc’s outlook.

Why was a shift to the right forecast?

Although the elections are contested on the basis of each country’s national parties, Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) sit in political blocs, ranging from the left to the right, rather than by nationality. This dynamic means that the direction of a country’s domestic politics will likely influence the electorate’s choice of MEPs that go forward to sit in the EP.

Ahead of June’s polls, a shift to the (far) right was forecast, reflecting wider and growing divisions in national politics, particularly in several European states. To give this a sense of precedent, since 1979, when the first EP polls were held, the far-right parties have enjoyed as strong a showing as they currently have.

Did the shift happen?

For all the talk of this being an election to watch, this failed to stir the more than 370 million voters. Overall turnout registered 51.06%, marginally higher than the 50.7% recorded in the last elections in 2019. This remains a respectable average figure when compared to other elections, such as US congress mid-terms. But it masks stark divergences with 89% in Belgium, where voting is mandatory, down to as little as 21% in the EU’s newest member, Croatia.

Right-wing parties made gains, but not to the extent that some had suggested. Indisputably, however, the number of far-right MEPs has grown, representing almost 15% of the vote.

Notably, there was a swing to the far right in EU’s six original member states, with a strong showing on the part of Austria’s Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPO), Belgium’s Vlaams Belang, France’s Rassemblement National (RN), and Italy’s Fratelli d’Italia. Failing to meet expectations and coming in second in Germany and the Netherlands were the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) and Partij voor de Vrijheid (PVV).

Elsewhere, however, the far right either failed to command a strong lead or existing parties held their ground. The EU’s eastern countries and those to the north, such as Denmark, registered a strong showing for left-wing and green parties at the right’s expense.

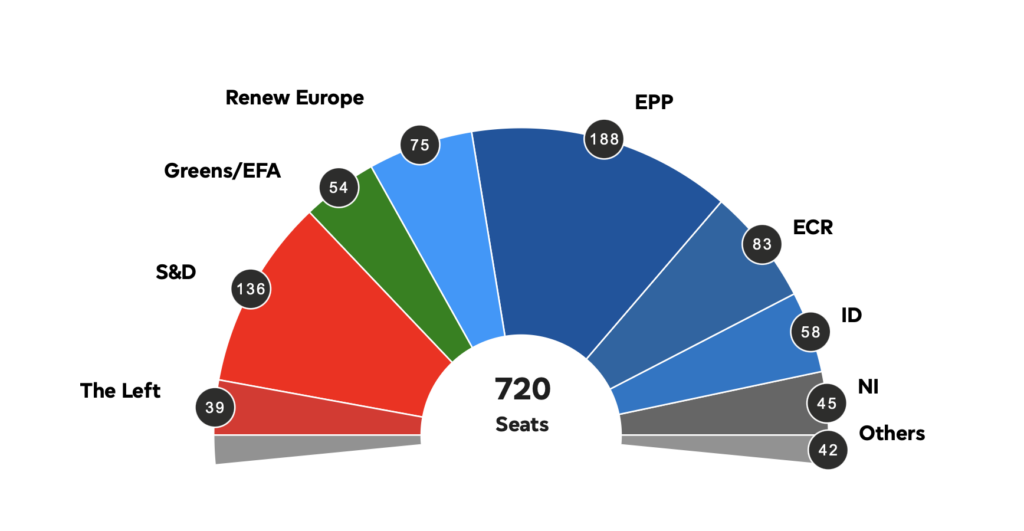

The majority lies with those parties that are broadly in the centre. If the Christian Democrats (EPP – the biggest party) continue to work with the Social Democrats, greens and liberals, they will command approximately 64% of the legislature (down from almost 70% previously).

Provisional results of the European Parliament elections 2024, Source: The European Parliament

The broader repercussions of the elections

There was undoubtedly a fall-out at a national level, most obviously in France. Following the poor showing of President Emmanuel Macron’s Renaissance party and allies, who secured about 15% of the vote, the president announced he would dissolve the national assembly, triggering national elections in a gamble to try to regain the impetus.

It is also unclear if the far-right parties will work together, which would in turn, expand their influence. Currently, they are a disparate lot, which undermines their possible clout. That said, Italian prime minister, Giorgia Meloni, has the potential to be a pivotal figure, both for the far-right parties and also in Brussels.

This is largely because she plays three leading roles – as head of Italy’s government, leader of Italy’s largest party, Fratelli d’Italia, and a key figure in the European Parliament’s centre-right European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) group.

As things stand, there are two parties to the right of the EPP – the ECR and ID. It remains to be seen whether attempts to create a new group – Patriots for Europe – will meet the geographic criteria to form another far-right group.

This ties into another aspect to consider, namely how the far-right agenda is entering mainstream politics. Typically, the centrist parties have worked together, but there’s the possibility that they may come under greater pressure to adopt tougher policies, thereby seeing an indirect influence rather than a direct one; it remains unlikely that any formal or regular collaboration between the centrist parties and the far-right parties will take place, given the comfortable working majority the former hold.

What do the election results mean for wider policy?

In general, a slightly more divided EP is expected to find it a little harder to reach consensus in key policy areas. Among the ones most widely discussed as top political priorities for the next cycle are the EU’s competitiveness, the outlook for environmental legislation, future funding and continued support for Ukraine, and the revitalized economic security agenda. Overall, however, there is not expected to be any major shift in policy outlook due to the EP election results.